Consider two starkly contrasting images: a vast expanse of land cultivated by hand using rudimentary tools, yielding just enough to sustain a meager existence for its inhabitants; and a sprawling metropolis humming with the activity of advanced industries, its citizens enjoying high standards of living and its corporations wielding influence across the globe. This juxtaposition encapsulates one of the most compelling puzzles in the study of nations: how does a society mired in agrarian underdevelopment, characterized by limited capital accumulation and basic technological capabilities, undergo a fundamental transformation to emerge as a high-wage, economically influential power? This essay delves into the intricate processes that underpin this remarkable journey, exploring the multifaceted drivers and consequences of national development.

1.2 Beyond Simple Growth: The Depth of Change

The transformation from an underdeveloped, agrarian state to a developed, industrialized nation transcends mere economic expansion. It entails a profound shift encompassing not only the quantitative increase in economic output but also a qualitative change in the very fabric of a nation. This essay posits that such a transformation involves deep-seated changes in economic structures, a fundamental evolution of societal values, the accumulation of national capabilities, and a significant alteration in the landscape of tastes and consumption. Our analysis, therefore, extends beyond traditional economic growth models to explore the intricate interplay of economic mechanisms, the gradual reshaping of cultural norms, the ascent of national power in the global arena, and the evolving patterns of what a nation produces and consumes.

1.3 Preview of Key Arguments

This analysis argues that the transformation from agrarian underdevelopment to developed status is a complex, multi-stage process shaped by a confluence of initial conditions, external catalysts, and internal transformations. We will first examine how the initial reliance on low-productivity agriculture and demographic pressures creates a cycle of poverty. Subsequently, we will analyze how external impulses, such as foreign direct investment and access to export markets, can act as catalysts for change, provided they are strategically adopted. The essay will further explore the internal transformations that reshape society and the economy, including urbanization, wage escalation, cultural shifts, and the maturation of institutions (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). A critical aspect of this journey is the ascent up the value chain, moving from basic production to innovation-driven activities. Finally, we will consider the implications of graduating from a cheap labor model and the complex question of whether all nations are destined to converge on a single model of development, acknowledging the persistent factors that lead to divergent paths.

2. Foundations: The Intertwined Origins of Underdevelopment

2.1 The Agrarian Trap and Demographic Pressures

Predominantly agrarian societies often find themselves trapped in a cycle of poverty. This is frequently exacerbated by high birth rates that create a surplus of low-skilled labor relative to the limited capital and industrial capacity available. In such economies, a large proportion of the population engages in agriculture, often characterized by rudimentary techniques yielding low productivity. This reliance on traditional farming methods, coupled with limited access to modern inputs and technology, results in low output per worker and consequently low incomes. The abundance of labor, facing scarce capital and limited industrial development, keeps wages depressed, hindering the accumulation of savings and investment necessary for economic diversification and industrialization. Social and cultural factors, such as traditional family structures valuing large families and limited access to education and family planning, often contribute to these demographic pressures, creating a formidable obstacle to escaping poverty.

2.2 Technological Backwardness and the Productivity Gap

A defining characteristic of underdeveloped nations is a significant technological gap compared to their more developed counterparts. This gap manifests in the absence of advanced machinery, modern industrial processes, and specialized know-how. Production often remains heavily reliant on rudimentary tools and manual labor, leading to significantly lower productivity levels. This technological asymmetry has profound implications: without access to and the capacity to utilize advanced technologies, nations struggle to produce goods and services efficiently and compete effectively in international markets. Low productivity limits economic output, perpetuating a cycle of limited investment in technological upgrading and hindering the nation’s ability to climb the technology ladder (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). This dependence restricts economic growth and diversification towards higher-value-added activities.

2.3 Rural-Urban Divide: Economic Disparities and Migration Drivers

Urban centers typically form when agricultural surpluses or trade hubs enable concentrated settlements, allowing surplus food or wealth to support non-agricultural roles like artisans or traders, which rural areas, with their focus on subsistence farming, rarely sustain. These settlements develop infrastructure, such as roads and markets, to facilitate trade and specialization, attracting resources unavailable in dispersed rural settings. These proto-urban areas then attract further investment, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of growth. Emerging urban centers benefit from initial advantages in infrastructure (transport, energy, communication) and early industrialization, attracting investment and jobs that offer higher potential earnings. This concentration of opportunity makes cities increasingly attractive, drawing resources and labor from surrounding areas. However, substantial income and opportunity gaps arise between these urban centers and rural agricultural areas, which are often characterized by low-productivity agriculture and limited access to services like education and healthcare. This disparity acts as a powerful “push” factor from the countryside and a “pull” factor towards cities, motivating individuals and families to seek better economic futures in urban areas, even if it means facing the challenges associated with rapid urbanization (discussed in Section 4.1). Over time, this migration widens the rural-urban divide, reinforcing urban dominance.

2.4 The Unequal Playing Field of Global Trade and Historical Legacies

Similar to urbanisation in principle, though different in scale, some nations secure early advantages through geography, resources, innovations or institutions, which compound over time via the Matthew effect – where initial advantages tend to accumulate further advantages, while those with initial disadvantages experience a worsening of their situation. Gambacorta and Segura (2020) describe this as a self-reinforcing cycle of inequality that shapes global development. Consider Mesopotamia: its fertile rivers supported agriculture, freeing labor for innovations like writing, which bolstered trade dominance. Mali leveraged gold deposits to fund intellectual hubs, drawing merchants and wealth. Athens’ democratic system fostered intellectual and naval progress, cementing maritime power. Britain’s research and development, paired with abundant coal and iron, enabled industrialization, compounding through innovations like the steam engine, which bolstered global trade and colonial power. These advantages enabled nations to reshape their environments in their favour. For instance, the Mongols’ military tactics fueled conquests, extracting tribute to finance expansion, propelling the Mongols further, while slowing their competitors. The Inca’s road networks centralized authority, extracting labor to sustain their empire. Britain’s industrial and naval edge powered colonialism, extracting resources to drive growth. These cases – from Mesopotamia to Mali, Athens to the Inca to the British – reveal a pattern: early advantages, like advantageous environments, ideas and innovations, once amplified, create self-perpetuating dominance via mechanisms like trade, conquest, and labor systems. Those who have more, are at an advantage to amass even more from those who have less, leading to a widening gap in developmental acceleration. It must be noted here that this perspective, somewhat simplifies historical causality and does not fully account for contingency or the eventual decline of leaders through losing their price competitiveness, internal divides, and acts of God.

3. Catalyzing Change: External Impulses and Strategic Adoption

3.1 The Double-Edged Sword of Capital Inflows

External capital, particularly Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), can play a pivotal role in catalyzing economic transformation by providing crucial financial resources for infrastructure development and early industrialization. Beyond money, FDI often brings management know-how, cutting-edge tech, and global market access, as Borensztein et al. (1998) highlight in their analysis. This influx can finance essential infrastructure (transportation, energy, communication), stimulate job creation, enhance human capital through training, and boost export capabilities. However, capital inflows carry inherent risks. Potential downsides include debt accumulation if terms are unfavorable or management is weak, exploitation of natural resources without regard for sustainability (Hasanov et al., 2020), and displacement of local businesses unable to compete with multinational enterprises. Sometimes, value addition within the host country remains limited if foreign firms primarily seek cheap labor or raw materials with minimal local integration. Therefore, strategic government policies are essential to maximize benefits and mitigate risks. These policies should aim to attract FDI in priority sectors, establish clear regulations, promote technology transfer and local value addition (Kinoshita, 2000), manage macroeconomic effects like exchange rate fluctuations, and ensure fair and sustainable investment terms, potentially including fostering green FDI (Alonso et al., 2024). Effective management, potentially including capital controls, may be needed to prevent instability.

3.2 Export Markets: Borrowed Demand and Vulnerabilities

Access to international export markets provides a crucial catalyst for early growth, offering vital demand before a strong domestic market matures. Export-Oriented Industrialization (EOI) leverages comparative advantages to produce goods for sale abroad, generating foreign exchange earnings (Rodrik, 2006). These earnings finance essential imports like capital goods and technology. EOI allows exploitation of economies of scale by producing for a larger global market, increasing efficiency. Furthermore, exposure to international competition can further drive technological progress and innovation as domestic firms strive to meet global standards. However, heavy reliance on export markets creates vulnerabilities. Economies become dependent on external demand, susceptible to global economic fluctuations and the conditions of major trading partners. Price volatility in international markets for export goods can significantly impact earnings. Additionally, nations face the risk of protectionist measures from developed countries restricting market access. Global trade agreements and institutions (like the WTO) aim to establish rules, reduce barriers, and resolve disputes, mitigating some risks. Nevertheless, developing countries must strategically navigate the complex global trading system to realize the benefits of EOI while managing its inherent dangers.

3.3 Technology Transfer and the Art of Absorption

In their initial transformation stages, developing nations often import lower-end technologies and established manufacturing processes. This provides a relatively quick route to building industrial capacity compared to relying solely on indigenous innovation. However, technology transfer is not passive; effective adoption requires active engagement and “learning by doing.” This involves imitating existing technologies, then adapting them to local conditions, resources, and market needs. Over time, this process fosters local technical skills, engineering capabilities, and organizational know-how, enabling a move beyond basic assembly towards more sophisticated production and eventually indigenous innovation. A nation’s “absorptive capacity” – its ability to recognize, assimilate, and apply new external knowledge commercially – is critical (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Mahoney, 2022). Factors influencing this include the workforce’s education and skills, the existing knowledge base, R&D investment (Kinoshita, 2000), and effective communication channels. Nations with stronger initial foundations in education and technology tend to absorb and benefit more readily. Therefore, strategic investments in education, vocational training, and R&D are essential to enhance absorptive capacity and leverage technology transfer for sustained development and movement up the technology ladder. Reverse engineering can also be a valuable tool in this process.

4. Internal Transformation: Reshaping Society and Economy

4.1 Urbanization: Concentration, Productivity, and Challenges

The rural-to-urban migration driven by economic disparities (Section 2.3) leads to a significant geographic concentration of labor, capital, and knowledge. This increased density fosters specialization and a greater division of labor, leading to significant productivity increases (Redding & Venables, 2003). The proximity of businesses and workers facilitates knowledge spillovers, boosting economic dynamism. Agglomeration economies—the benefits derived from clustering economic activity—further enhance productivity and attract investment. However, rapid urbanization presents significant challenges as an outcome. The influx of people can strain existing infrastructure (housing, transport, sanitation, energy), often leading to inadequate provision and the growth of informal settlements. Inequality within cities can become pronounced, with visible disparities in income, access to services, and living conditions. Environmental degradation, such as air and water pollution, can worsen due to concentrated industrial activity and population density. Moreover, concentrating economic power in cities can exacerbate regional disparities if not managed carefully. Addressing these consequences requires strategic urban planning, significant infrastructure investments, and policies promoting inclusive growth and environmental sustainability.

4.2 Wage Escalation and the Gradual Rise of a Middle Class

Sustained economic growth, fueled by industrial expansion and urbanization, typically tightens the labor market. As demand for labor increases and the supply of readily available unskilled rural labor diminishes, wages begin to rise. This escalation is often supported by increased worker bargaining power and potentially the emergence of labor unions. Government policies like minimum wage laws and labor protections can also contribute. Rising wages significantly impact the economy by fueling domestic consumption, as workers have more disposable income. This increased consumption drives further economic activity and develops domestically-oriented industries, reducing reliance on external demand. As wages continue to rise and living standards improve, a middle class gradually expands. This growing middle class becomes a major driver of economic growth, demanding a wider range of goods and services (education, healthcare, consumer durables). However, initial skill disparities can lead to uneven wage growth, potentially creating persistent inequalities that require attention through education and skills development policies.

4.3 Cultural Evolution: Shifting Values and Aspirations

Rising wages and changing economic structures not only fuel growth but also reshape societal values. As workers gain disposable income (Section 4.2), consumerism often increases, and aspirations shift towards education, skill acquisition, and material improvement, driving cultural evolution. Higher wages not only increase consumption but also cultivate a culture of aspiration and education. Economic transformation is deeply intertwined with this cultural shift. As societies industrialize and urbanize, traditional values often associated with agrarian life may gradually give way to norms more suited to an industrial, market-based economy. Increased education levels, exposure to global media, and changing work structures can lead to shifts in attitudes towards family size, gender roles, individualism, and risk-taking. Aspirations change; emphasis may shift from subsistence and community stability towards individual achievement and upward mobility. This cultural shift can reinforce economic development by fostering entrepreneurship, innovation, and a workforce adapted to industrial discipline. However, this transition can also create social tensions as traditional structures and values are challenged.

4.4 Infrastructure Development and the Maturation of Institutions

Sustained development requires not only physical capital but also robust infrastructure and effective institutions. Early investments, often spurred by FDI or export earnings, focus on basic infrastructure like ports, roads, and power generation. As the economy matures, the need shifts towards more sophisticated infrastructure, including advanced telecommunications, logistics networks, and specialized industrial parks. Simultaneously, institutions must evolve. This includes establishing secure property rights, enforcing contracts, developing a stable legal and regulatory framework, managing public finances effectively, and combating corruption (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). Mature financial institutions are crucial for mobilizing savings and allocating capital efficiently. Strong educational and research institutions become vital for fostering innovation and human capital development. The co-evolution of infrastructure and institutions provides the essential backbone for a complex, high-productivity economy.

5. Ascending the Value Chain: From Imitation to Innovation

5.1 Surplus Generation and the Growth of Domestic Demand

As productivity increases through industrialization and technological upgrading, nations begin to generate economic surpluses beyond basic subsistence needs. Rising wages and the growth of the middle class translate this surplus into expanding domestic demand. Consumers seek not only more goods but also higher quality and greater variety. This burgeoning internal market provides a crucial new engine for growth, reducing dependence on volatile export markets. Firms increasingly orient production towards meeting domestic needs, leading to diversification of the economy and the development of consumer goods industries, retail sectors, and service industries. This shift towards domestic demand creates a more stable and resilient economic base.

5.2 Industrial Upgrading and the Forging of Innovation Cycles

Successful transformation involves moving beyond simple manufacturing and assembly towards higher-value-added activities. This process of industrial upgrading requires continuous investment in technology, skills, and R&D. Initially, firms may focus on process innovation (improving efficiency) and minor product adaptations based on imported technologies. Over time, as absorptive capacity grows (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990) and local capabilities develop, the focus shifts towards more substantial product innovation and eventually to creating fundamentally new technologies and industries. This transition from imitation to innovation is critical for sustaining long-term growth and competitiveness. It requires building a national innovation system, encompassing universities, research institutions, private sector R&D, and supportive government policies that encourage risk-taking and protect intellectual property.

5.3 Capital Formation and the Sophistication of Financial Systems

Ascending the value chain necessitates significant capital investment. As the economy grows, domestic savings rates tend to rise, providing a larger pool of capital for investment. Concurrently, financial systems must become more sophisticated to effectively mobilize these savings and allocate them to productive uses. This involves the development of diverse financial institutions (banks, stock markets, venture capital funds) and instruments. A well-functioning financial system is crucial for funding large-scale industrial projects, supporting R&D activities, financing innovation, and managing economic risks. The ability to efficiently channel capital towards its most productive uses is a hallmark of a developed economy.

6. Strategic Assertion: Economic Strength and Global Influence

6.1 Military Modernization and the Pursuit of Strategic Autonomy

As national economic power grows, states often seek to enhance their strategic autonomy and influence on the global stage. Increased national income allows for greater investment in military modernization, including acquiring advanced weaponry, developing indigenous defense industries, and professionalizing armed forces. This enhanced military capability can serve various strategic goals, such as deterring potential adversaries, protecting trade routes and economic interests abroad, projecting power regionally, and increasing diplomatic leverage. The pursuit of strategic autonomy reflects a nation’s desire to act independently in international affairs, free from undue influence or coercion by other powers.

6.2 Geopolitical Leverage: The Strategic Importance of Key Industries and Resources

Economic development often involves cultivating strategic industries or controlling key resources that provide geopolitical leverage. Dominance in critical sectors (e.g., advanced technology, energy, finance) can translate into significant international influence. Nations may use their control over essential goods, technologies, or supply chains to achieve foreign policy objectives or gain advantages in international negotiations. Similarly, control over vital natural resources can be a source of power, although it also carries risks of dependency (the “resource curse”) if not managed strategically. Strategic management of these economic assets becomes an integral part of a nation’s foreign policy toolkit.

6.3 Monetary and Capital Market Expansion: The Potential for Global Financial Influence

Advanced economies often develop deep, liquid, and internationally integrated financial markets. As a nation’s currency becomes more widely used in international trade and finance (potentially achieving reserve currency status), and its capital markets attract significant foreign investment, its influence over global financial flows increases. This can provide advantages such as lower borrowing costs and greater macroeconomic policy flexibility. Major financial centers can shape global financial regulations and norms. However, global financial integration also exposes the economy to international financial shocks and requires sophisticated regulatory oversight.

7. Case Studies: Diverse Pathways and Common Threads

7.1 Britain: The Interplay of Resources, Innovation, and Global Reach

Britain’s early industrialization leveraged abundant coal and iron resources, coupled with key technological innovations like the spinning jenny and steam engine (Section 2.2). Its transformation was propelled by enclosure movements pushing labor towards cities (Section 2.1), where rapid urbanization concentrated the workforce and boosted productivity. Early development of property rights and financial institutions (Section 4.4), alongside a vast colonial empire providing raw materials and captive markets (linking Sections 2.4, 3.2), further fueled growth. Its global reach facilitated capital accumulation and export-driven growth but also established patterns of unequal trade, illustrating how Britain’s early advantages compounded through its empire, demonstrating how initial strengths can amplify over time. This pathway highlights the role of both internal factors (innovation, institutions, urbanization) and external exploitation in early development.

7.2 Germany: The Synergy of Education, Industry, and State Strategy

Germany’s later industrialization emphasized heavy industry (steel, chemicals) and was strongly supported by state strategy. Key elements included significant investment in technical education and R&D, enhancing absorptive capacity (Section 3.3), the development of universal banking providing close ties between finance and industry (Section 5.3), and protectionist policies shielding nascent industries (linking Sections 3.3, 4.4, 5.2). Germany’s path demonstrates a successful state-led catch-up model focused on building human capital and technological prowess, suggesting a different route to convergence than Britain’s market- and empire-driven approach.

7.3 Japan: Strategic Adaptation and Indigenous Development

Following the Meiji Restoration, Japan embarked on rapid, state-led modernization. It strategically imported and adapted foreign technology (“learning by doing,” Section 3.3), invested heavily in education, and fostered large industrial conglomerates (zaibatsu/keiretsu). Post-WWII, its focus on export-oriented manufacturing (electronics, automobiles), rigorous quality control (Kaizen), and process innovation, supported by government-industry cooperation (MITI), drove its ascent (linking Sections 3.2, 3.3, 5.2). Japan’s development emphasized adaptation, incremental improvement, and a unique cultural focus on quality, creating a distinct, highly competitive industrial model that challenged Western dominance and offered another alternative pathway.

7.4 China: Scale, Strategic Direction, and Global Integration

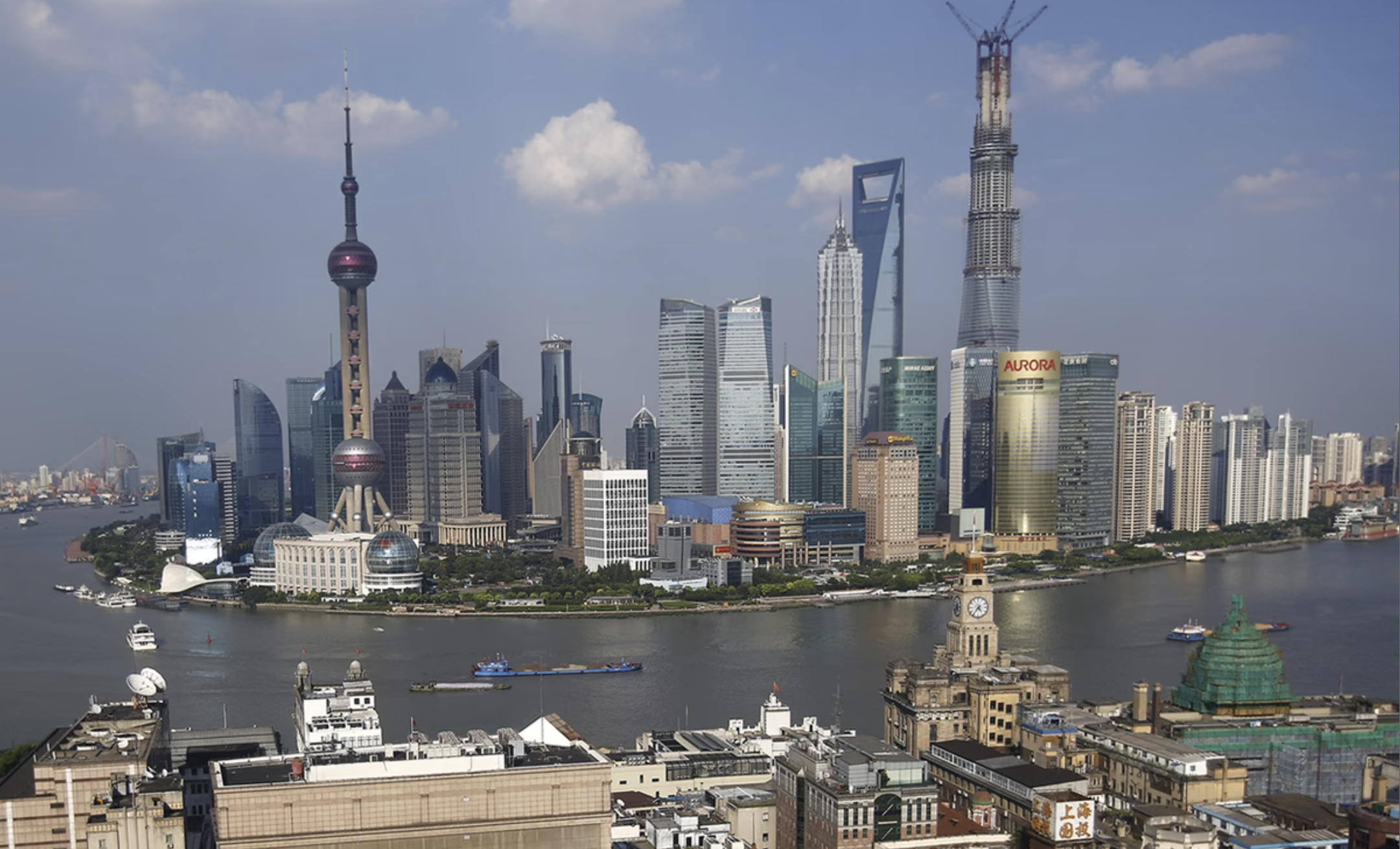

China’s transformation leveraged its immense scale, providing a vast pool of low-cost labor (Section 2.1) and a potentially huge domestic market (Section 5.1). State direction played a crucial role, initially focusing on attracting FDI for export-oriented manufacturing (Sections 3.1, 3.2) through mechanisms like the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone – which achieved average annual growth rates exceeding 20% (Ye, 2021)in its early decades – and massive infrastructure investment (Section 4.4). Strategic use of these zones facilitated technology transfer and integration into global supply chains (Section 3.3). More recently, China emphasizes indigenous innovation (“Made in China 2025”) and shifting towards domestic consumption (Sections 5.1, 5.2, 8.2), demonstrating a dynamic adaptation of strategy over time and presenting a powerful example of state-capitalist development diverging significantly from liberal market models.

7.5 Transition

These cases highlight common stages but varied strategies and outcomes, shaped by initial conditions, strategic choices, and global context. Britain pioneered an early, resource- and empire-driven model accelerated by urbanization; Germany focused on state-backed industrial and educational strength; Japan excelled through adaptation and quality; and China leveraged scale and state direction with remarkable speed. This diversity challenges notions of universal convergence and raises the fundamental question explored next: do these varied paths ultimately lead to a single development endpoint, or does divergence persist?

8. The Finite Nature of Cheap Labour Advantage and the Question of Convergence

8.1 Labour Market Tightening and Demographic Transition: The Inevitable Rise of Costs

The comparative advantage derived from abundant, low-cost labor is inherently finite. As industrialization progresses and rural-to-urban migration slows, labor markets tighten, leading to upward pressure on wages (as discussed in 4.2). Simultaneously, successful development often leads to demographic transitions—falling birth rates and an aging population—which further reduce the supply of young, low-cost workers. This necessitates a shift away from labor-intensive industries towards more capital-intensive and knowledge-based activities to maintain competitiveness.

8.2 The Ascendancy of Consumer Power and the Pivot to Domestic Markets

As wages rise and the middle class expands (Section 4.2), domestic consumers gain significant purchasing power. This growing internal market becomes increasingly important as an engine of growth, particularly as the cost advantages in export markets diminish. Nations at this stage often pivot strategically, encouraging domestic consumption and developing industries and services tailored to local tastes and needs. This shift provides greater economic resilience compared to heavy reliance on external demand.

8.3 Political Consolidation and the Pursuit of Strategic Ambition

Economic success often strengthens the state’s capacity and legitimacy. Governments may leverage increased resources and national confidence to pursue more ambitious domestic and international goals. This can include expanding social welfare systems, undertaking large-scale national projects, asserting greater regional or global influence (Section 6), and potentially adopting more nationalistic or assertive foreign policies. For instance, China’s economic success has arguably bolstered its government’s legitimacy, enabling ambitious projects like the Belt and Road Initiative and a more assertive foreign policy stance, illustrating how economic development can intertwine with political objectives. Political consolidation can provide stability but also carries risks if power becomes overly concentrated or unresponsive.

8.4 The Limits to Global Convergence: Divergent Paths and Persistent Differences

While the broad stages of transformation share common elements, the idea that all nations will inevitably converge towards a single model of high-income, liberal-democratic capitalism is questionable. Initial conditions, historical legacies (Section 2.4), cultural factors (Section 4.3), institutional choices (Section 4.4; Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012), geopolitical contexts, and strategic decisions made along the way lead to diverse development pathways. Some nations, like Singapore with its highly effective state-led model or China with its state-capitalist approach, prioritize state control over market liberalization, emphasize different industrial specializations, or maintain distinct political systems even at high levels of income. Persistent global inequalities and compounding advantages also suggest that catching up remains challenging for many, reinforcing the potential for divergence rather than uniform convergence.

8.5 The Spectrum of Development and the Importance of Context

Development is not a binary state (underdeveloped vs. developed) but rather a spectrum. Nations occupy different positions along this spectrum, and their specific challenges and opportunities depend heavily on their unique context. Factors like resource endowments, geographic location, political stability, social cohesion, and historical relationships shape the available pathways. Therefore, development strategies must be context-specific, recognizing that there is no one-size-fits-all formula for successful transformation (Rodrik, 2006).

9. Conclusion: The Evolving Landscape of Global Economic Development

9.1 Synthesis of Key Findings

This essay has argued that the transformation from an agrarian society to a developed industrial power is a profound and multifaceted process. It begins with overcoming the foundational challenges of low productivity, demographic pressures, and often unfavorable historical legacies. Catalyzed by external impulses like capital inflows and export opportunities—if strategically managed—nations undergo deep internal transformations involving urbanization, wage growth, institutional maturation, and cultural shifts. Sustained progress requires ascending the value chain through technological absorption, industrial upgrading, and ultimately, innovation, increasingly driven by domestic demand. Economic strength often translates into greater geopolitical influence.

9.2 The Enduring Influence of Initial Conditions

Starting points significantly shape the transformation. Historical context, resource endowments, and early institutional choices (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012) create path dependencies that mold subsequent opportunities and constraints. Advantages, once gained, can compound, making it difficult for latecomers to close the gap entirely, highlighting the persistent relevance of initial conditions in global development patterns.

9.3 The Complex and Contingent Nature of Development

The transformation process is neither linear nor guaranteed. It involves navigating complex interactions between economic forces, social changes, political decisions, and global dynamics. Success hinges on strategic choices, effective institutions, adaptive capacity, and often, a degree of fortune. The diverse experiences illustrated by the case studies underscore that while common themes exist, each nation forges its unique path.

9.4 Final Thoughts on Global Convergence and the Future of Development

While economic development leads to significant improvements in living standards, the notion of universal convergence towards a single endpoint appears unlikely. Divergent paths persist, shaped by enduring cultural, political, and historical differences. Looking forward, emerging factors like digitalization, artificial intelligence (AI), climate change, and shifting geopolitical alignments will undoubtedly reshape the landscape of national development. For example, AI could disrupt labor markets by automating industries, requiring new skills and reshaping work, while transformative policies, such as those on climate change, can fundamentally shift industrial practices, altering comparative advantages and demanding innovative responses (Alonso et al., 2024). Understanding the complex, contingent, and context-dependent nature of the transformation journey remains crucial. Nations must adapt context-specific policies, leveraging lessons from diverse pathways to foster inclusive and resilient development and thrive amid these profound global shifts.

Thanks for reading and, as usual, find my sources here.