“In an age where there’s so much active misinformation and it’s packaged very well, and it looks the same when you see it on a Facebook page or you turn on your television, if everything seems to be the same and no distinctions are made, then we won’t know what to protect.” – Barack Obama. This quote is from a speech by Obama in 2016. 7 years ago, the quality of misinformation had already reached the level at which an observer had serious difficulty differentiating between what is correct and what is not. There are several reasons for the spread of misinformation, such as polarisation, a lack of media literacy and confirmation bias. However, this essay will look at the problem as societal development being sacrificed for political and economic gains, with an emphasis on new/social media in the West.

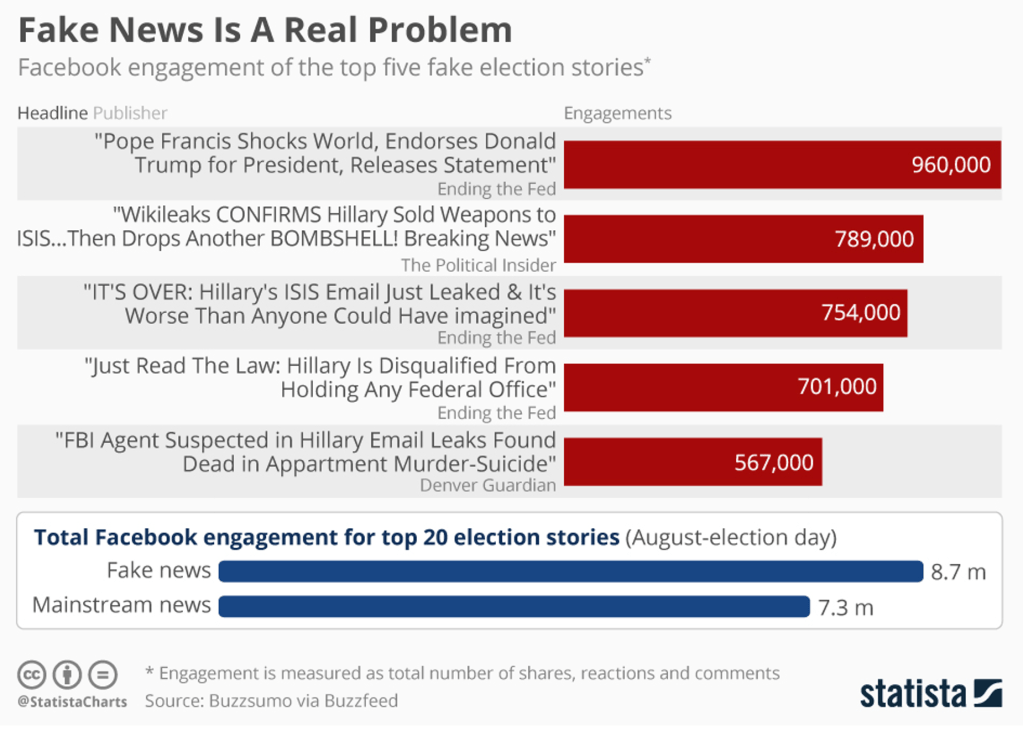

In 2023, technological development has increased the production speed of misinformation, its quality, and finally, its reach, beyond what has been seen before. Individuals on social media are now able to reach as many readers as the BBC or CNN (Borella & Rossinelli, 2017). This advancement in technological sophistication in media and communication has been so significant that it has been given the name Second Gutenberg Revolution by some. In addition to that, both corporations and the political industry, have become more adapted to – and open to use – misinformation as a standard practice, leading to its omnipresence (Compare Figure 1 & 2). Some earlier adaptors such as intelligence agencies have long achieved ubiquity in spreading misinformation (Peters, 2017). As a result, media output has become driven by the pursuit of commercial and political profit, rather than truth.

One of the many problems with prioritising profit over truth is that issues, particularly those that have been politicised, are not being effectively addressed. Because false information is being disseminated, a false reality is created within the minds of the consumers of that misinformation. Because of the universal penetration through the means enabled by the Second Gutenberg Revolution, the majority of Western civilisation is exposed to misinformation. In a study by PEW Research, 64% of US adults said misinformation has caused “a great deal of confusion” about the basic facts of current events (Barthel et al., 2016). This false reality leads to the consumers directing their energy towards an untrue definition of the problem, thus not solving it efficiently. Solutions crafted for a problem that isn’t truthfully described and stated will inevitably lead to more problems (West & Bergstrom, 2021). One must also mention that while the untrue problem is being solved, the real problems are not being solved or mischaracterised. Further than that, the misinformation often works towards commercial and political agendas that can be contrary to creating development and peace. With multiple players creating multiple misinformation campaigns claiming different statements, one can also see how a division of the population takes place between the followers of each of the false narratives.

In conclusion, while there are several reasons for the spread of misinformation, including polarization, a lack of media literacy, and confirmation bias, this essay examines the problem of societal development being sacrificed for profits, both in terms of political and monetary gains. Solving the problem of widespread misinformation lies at the core of enabling a productive and progressive society, not solving it leads to the contrary.

Stakeholders

The stakeholders can be classified into two categories, the active stakeholders and the passive stakeholders. The active stakeholders are those who actively work to create the problem, whereas the passive stakeholders are the people that are experiencing the problem without actively contributing to it.

Active Stakeholders

The first notable stakeholder is the media industry. The media industry is distributing information to the masses and can control what reaches the masses and what does not. The media industry consists of legacy media and new/social media. The majority of Western Media is owned by six companies (Compare Figure 3).

Further than that, the ownership structure of these six companies reveals that Vanguard and Blackrock are in the top three of the largest stakeholders in all of the six, but National Amusements – meaning the two investment firms have significant voting rights and power in the five firms. Vanguard and Blackrock both are custodians of the stock of their clients (Reuters Fact Check, 2022). They both are businesses that exist to maximise value for their clients, their business model is based on making decisions that increase dividends & value of the companies they own. This is also true for each of the six media companies on their own. By definition, these businesses’ purpose is to maximise shareholder value, not to accurately deliver truthful information to enable society to flourish. However, their media channels are often presented as truthful sources of information and thus passive stakeholders can be misled.

This introduces the second stakeholder, the largest companies within the global industrial complex. They are invested in using media as a part of their advertisement or communications to increase profits. They craft narratives around their products and dispense them directly and subliminally throughout media to nudge the consumer to buy their products and services. Examples include the tobacco industry; In 1980, four of the biggest American tobacco corporations came together to place their products in movies and television. Efforts were undertaken to create favourable press around cigarettes throughout the 80s and 90s (Mekemson & Glantz, 2002). Another similar example of an industry group investing in swaying public opinion through the media is the dairy industry and its narrative that milk is beneficial for one’s health (Belluz, 2015). Thus, the most influential parts of the global industrial complex, whether it is the dairy-, tobacco-, energy-, pharmaceutical- or sugar industry, are all highly invested in shaping the narrative through the media as a core part of their sales strategy.

Stakeholder three is the political industry. This stakeholder is comprised of politicians from all parties, including nationalists and populists, supported by communications, intelligence agencies and public relations employees. Their goal with regards to media is to use it to shift public opinion in favour of their party’s agenda, or themselves[1]. Cambridge Analytica and the recent Twitter files have shown how political parties from both the right and the left, foreign and national, try to exercise control over what information reaches the masses, and what information is being suppressed. The Twitter files have shown that the FBI has the power to censor and manipulate social media, as Wallace-Wells (2023) reports: “Fang discovered that Twitter had long been cooperating with the Pentagon to help the U.S. government amplify accounts (often in Arabic or Russian) with friendly, and sometimes manufactured, perspectives.”. Furthermore, the ties of the political system to legacy media, through access journalism, political endorsements, regulatory capture, lobbying and advertisement have been long established.

Passive Stakeholders

The consumer of all kinds of media is the voter in elections, the customer to the corporations and finally, the last stakeholder. Through the tactics described in the previous section, the active stakeholder influences the passive stakeholder. The quantity & quality of media aimed at manipulating consumers has increased significantly, and people now consume more media than ever before.

Major Debates & Issues

Responsibility of Social Media

The responsibility of social media platforms has become a major point of debate in the context of misinformation. Some argue that social media platforms should be held accountable for the spread of misinformation on their platforms because they have the power and influence to shape public opinion and impact democratic processes (Bursztynsky, 2021). Others argue that social media platforms are merely neutral platforms and that it is the responsibility of individuals to be critical consumers of information (Forrester, 2023). In the US, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, provides platforms immunity for content posted by third parties, however with the problem intensifying regulatory steps are becoming more likely (Vese, 2021 & Gielow Jacobs, 2022).

Those who argue that social media platforms have a responsibility to address the spread of misinformation usually advocate for more regulation and moderation of social platforms (Vese, 2021). They argue that social media companies should be held to a higher standard of accountability and that they should be required to take proactive measures to prevent the spread of false information (Paul, 2020). Proposed solution approaches include increased fact-checking, labelling of false information, labelling of correct information, and removal of content that is deemed to be false or harmful (Paul, 2020).

However, there are also concerns that social media platforms are not able to determine what constitutes false information. Additionally, concerns about free speech and freedom, core values of Western civilization, are raised with regard to regulating social media, making the debate highly politicised. Some argue that regulating social media could threaten free speech, and statements such as that from US Senator McCain: “When you look at history, the first thing that dictators do is shut down the press.” (Reuters Staff, 2017), emphasize the importance of protecting free speech.

Democracy

“’I am concerned right now the future of our democracy is in the hands of very few people at these tech companies,’ said Lisa Fazio, a professor at Vanderbilt University who studies the spread of misinformation.“ (Paul, 2020). Stakeholders including foreign intelligence agencies[2] and national political parties[3] are highly interested in shaping the discourse around democratic elections. Democracy is based upon trust in the population to choose their leaders wisely. As described in Section 1, there is a fundamental issue with how people’s decisions are informed, which in turn impacts their voting decisions and democratic principles.

On the one hand, some argue that free speech lies at the core of democracy and must be protected as an absolute. On the other hand, free speech allows misinformation of all kinds to spread freely and without consequences, leading others to argue that it must be limited to ensure a functioning democracy (Gielow Jacobs, 2022). A third group advocates for media literacy and education, as well as organizations to oversee public discourse (Edwards, 2022). This debate occurs at a general level, but more recently, there has been a particular reference to social media and the role of tech companies in relation to these arguments (Mattoo, 2022).

For passive stakeholders, the essential debate revolves around how they can be protected from being misinformed and manipulated while making sure that there is no Orwellian institution, or a group of tech executives, that has full control over the information that they receive.

Proposed Solutions

There are several approaches to solving the issues of the ubiquity of misinformation in social and legacy media. Elon Musk’s Twitter proposes to allow almost everyone to have a voice on the platform. Jack Dorsey’s BlueSky supposes decentralisation as the solution. Legacy media proposes an array of add-ons that are supposed to tell the reader what is true and what is not.

Elon Musk and Twitter

Firstly, and most famously, Elon Musk’s Twitter is the platform where a lot of the discussion on Sections 3.1 & 3.2 has been happening. Musk’s first approach to solving the problem is awareness. Through an array of tweets he released, and the Twitter Files, Musk made a large number of individuals aware of the degree of misinformation and manipulation they had been exposed to, or at least nudged them to question their sources (Malik, 2023). Since a large part of misinformation relies on the passive stakeholder being unaware of its existence as a lie, this is an efficient strategy to nudge more people to think critically about what they consume in general. It is important to note, Musk is not the only person that has been doing this.

Following the Twitter Files, Elon Musk began unblocking voices that had been previously censored on the platform, these included individuals such as Jordan B Peterson, who have been speaking out against many of the narratives told by the active stakeholders and for open discussion and dialectics. Allowing different viewpoints to confront each other on a platform like Twitter can be useful as the observer can see both sides in a conversation and gain an understanding beyond one party.

It must be noted that the above is the strategy Musk claims to be following, however, several journalists have pointed towards differences in what he says and what the data shows[4].

Jack Dorsey and BlueSky

The BlueSky team, led by Jack Dorsey, is building a social media protocol and app, called BlueSky. The protocol is like an operating system that social medias can use as their underlying infrastructural network (Frenkel, 2023). BlueSky aims to create an open and decentralised standard for social media, which should allow for greater transparency and accountability. Dorsey stated his intention to open source the project, meaning everyone would be able to contribute to and use the protocol (Palmer, 2019).

Most social media platforms, and all the big ones such as Facebook, TikTok, Instagram & Snapchat are centralised, meaning they are operated & owned by one corporation that makes the decisions about the platform[5]. In contrast, BlueSky is decentralised, meaning that it is not controlled by a single company but by a network of users and nodes[6]. This means to access and use the platform users will not need to access it via the controlling corporation’s servers. Instead of the corporation, the community of users will be able to collectively decide how the platform is run and what it allows and doesn’t. Because these decisions are happening on the public blockchain, every user can see the platform’s rules (Garrett, 2023).

Legacy Media’s Solution

Legacy media includes newspapers, magazines, television, radio and books. There are several different ways in which the problem of a post-truth world in media and politics is being handled in legacy media. These approaches include fact-checking operations, ethical guidelines, collaborations with NGOs and audience engagement.

The Washington Post has invested in fact-checking operations to help counter misinformation and fake news (Kessler, 2017). The fact-checking teams evaluate the accuracy of statements made by politicians and public figures. In turn, the Associate Press has a fact-checking team that examines claims made in the news (Associate Press, 2023).

Several legacy media organisations, including the New York Times, BBC and CNN have developed ethical guidelines for their journalists and news organisations. These guidelines are shaped around issues such as accuracy, impartiality, transparency, integrity and professionalism (New York Times, 2019).

The New York Times has formed a partnership with news organisations in other countries to share reporting expertise and resources following the academic principle of peer reviews.

Many legacy media organisations such as The Guardian, NPR and the BBC have invested in initiatives to engage with their audiences and to promote dialogue and discussion. This includes initiatives such as reader comment sections, social media engagement, and community events.

Personal Opinion

Legacy media’s approaches all help to combat misinformation, by exposing certain fake news stories and falsehoods. However, one must not forget that as explained in section 2.1 all these businesses have their shareholder’s profit as a priority, as opposed to strictly telling the truth. Over-stylized and politicised stories sell well, which is why they will continue to be broadcasted. Findings published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA (PNAS) also found that fact-checking and labelling efforts may not be effective in changing people’s beliefs (Kozyreva et al., 2023). I see legacy media’s attempts to “solve” the issue as more of a reputation-management and power-protecting tool than an actual effort to increase their level of neutrality and truthfulness. As demonstrated in the example of Musk in Section 4.1, any of the large media companies can claim that they are on the side of the truth. However, there is no way for a passive stakeholder to truly verify this claim using the solutions provided by legacy media. While these actions attempt to address misinformation on the surface, they fail to address the deeper issue of an entire company having a bias or agenda that they do not openly admit to following.

Concerning Twitter’s proposed solution, on the one hand, the degree of freedom of speech is going to produce misinformation and posts certain people might find offensive. On the other, I think it is valuable to have a platform where all information, including misinformation, can flow freely. This is because people are incentivised to use and train their sense of discernment, rather than relying on the company to do it for them and trusting that whatever they report is the truth. According to Akomolafe et al. (2017), the truth is subjective, with which I can agree to an extent. Allowing all voices on a platform enables people to discover all of these different truths, or stories. However, the issue with Twitter is that it is still owned by a single individual with executive powers over the platform. While Musk may claim to make Twitter a neutral ground, the company could still manipulate and censor at any time as it did under Dorsey’s leadership (Wallace-Wells, 2023). However, if a BlueSky-style protocol was implemented on Twitter or other platforms users can instantly become aware of the degree of manipulation that is occurring on the platform without having to rely on the words of a CEO with centralised power such as Musk. As mentioned in 4.1, making people aware of the exitance of manipulation and different stories is essential to solving the problem. I think the solution will lie in an online platform that has implemented a system, like what BlueSky claims to become, that allows for decentralised control and transparency. Finally, if ownership is decentralized among a large number of users on a platform with a mission to neutrally inform, the pursuit of small incremental profits could become less important to each user than the value of being able to source truthful information.

Opportunities for Business & Adaption

In addition to building the platform described in 4.4, akin to BlueSky, there are several business opportunities across industries, some of which can be put into action right now.

Neutral Consumer Fact-Checking Tools

Section 4.3 highlighted the issue with the fact-checking tools provided by the big media companies themselves, this opens a business opportunity. Businesses could commit to neutrality and demonstrate it by fact-checking all political sides. Businesses could adopt either a subscription-based model where customers pay to use their service, such as a browser extension, or a business-to-business model where independent journalists and media groups pay to have their articles fact-checked by a neutral party, thereby strengthening their authenticity.

Creating Alternative Narratives – Supporting Independent Journalists

In a post-truth world, independent journalists, who investigate the stories put out by the active stakeholders, are in high demand. Many passive stakeholders seek independent reports since a lot of the trust they had in the big institutions has been lost. This creates an opportunity for both, individuals to become independent journalists and for organisations to unite independent journalists and publish them.

Corporate Governance – Building Trust

Businesses must build trust, no matter whether they are operating in a truth or post-truth world. However, particularly in a post-truth world, building trust becomes important. This is because consumers are becoming aware of the flaws and lies in the mainstream narratives and seek alternatives they can trust. Providing such an alternative has proven highly profitable, as the case of Jordan B. Peterson shows, who has become one of Canada’s best-selling authors by providing an alternative to the cultural narrative set by the active stakeholders (Hopper, 2018). Businesses based on a public persona, such as Peterson’s as well as SMEs that do not belong to the active stakeholders must reconsider who they want to align with – the mainstream narrative or an alternative. Aligning with an alternative creates the opportunity to build a community that is unified behind a common idea of reality, truth and purpose that sets them apart from all other businesses and opens the door to deep partnerships and collaboration in their alternative niche. This increases the stickiness of customers significantly and thus provides a profitable option. An example of the successful execution of that business model is the Daily Wire. The Daily Wire built its business around highlighting the issues and lies with the active stakeholder’s liberal narratives in particular, notably with a strong favour towards the conservative side. Started by one presenter, Ben Shapiro, the network now has 115 employees, produces TV shows and movies and offers its own streaming service that has around one million paid subscribers (Meek, 2022). The strength of this business model lies in the creation of a community of consumers that is united in their views, set apart from the mainstream.

Generally, businesses will have to become more transparent and truthful as consumers increasingly question their actions and hold them accountable publicly. Particularly as platforms are being created where passive stakeholders can speak uncensored. Additionally, an economy based on fact-checking and discovering the truth as well as exposing falsehoods is being created, which is one more reason for businesses to follow a more truthful course of actions.

Conclusion and the Future

In conclusion, the problem of societal development being sacrificed for political and economic gains is a deep and widespread one. It is not a problem which can be pointed to a single political or corporate entity. It is a problem that is a result of the structure of the world that we built (Jerit & Zhao, 2020). The problem has had serious impacts, on elections, public opinion, consumer behaviour and public education. Because of the nature of this problem, there isn’t one solution to solve it. However, as this essay has tried to present a solution to some of the issues with regard to its technological focus on social/new media, a decentralised, transparent platform seems to be the answer to some of the associated problems.

The debate surrounding race and identity has prompted many individuals to think beyond established norms. Immigration and urbanization have exposed people to diverse opinions and cultures, while new wealth measures proposed by Amartya Sen challenge singular profit-focused measurement systems and encourage a new understanding of collective goals. The emergence of new forms of work driven by AI and the impact of the pandemic have also sparked a conversation about the state and future of our lives, prompting us to question our purpose. All of these topics have led people to consider alternative perspectives, making it more important than ever to determine which sources of information to trust, as the once-centralized, all-knowing, and trusted institutions seem to be a thing of the past. Combining that outlook with the possibilities new technologies bring, such as decentralization via blockchain, can result in some paradigm-shifting innovations occurring within the next decades.

[1] As Peter Vanderwicken wrote in 1995, for the Harvard Business Review: “The news media and the government are entwined in a vicious circle of mutual manipulation, mythmaking, and self-interest. Journalists need crises to dramatize news, and government officials need to appear to be responding to crises. Too often, the crises are not really crises but joint fabrications. The two institutions have become so ensnared in a symbiotic web of lies that the news media are unable to tell the public what is true and the government is unable to govern effectively”

[2] An example of that is the accusation against Russia, alleging that they have been engaged in misinformation campaigns to alter the course of the US election in their favour (BBC, 2018). The Kremlin has also been accused of doing so in UK elections (Peters, 2017).

[3] Nationalists and populists have also made use of misinformation campaigns to make misleading claims about immigration, portraying immigrants as a drain on social services and the economy as a whole (Lowrey, 2018). While the statement is contrary to a wide range of investigative findings (Sherman et al., 2019), echo chambers and nationalist and populist active stakeholders have heavily relied upon these false narratives to fuel their popularity and arguments.

[4] Forbes reported that post-Musk, Twitter has complied with over 80% of government and court requests for censorship, marking a 30% increase from the pre-Musk era where the figure was 50% (Hamilton, 2023). Musk is deeply connected to the US government through SpaceX’s government contracts, with NASA, the US Air Force and the National Reconnaissance Office, making a good relationship with the government a necessity for the success of Musk’s SpaceX (Grush, 2023).

[5] In the case of the named platforms, Meta, ByteDance & Snap Inc.

[6] A node is a participant in the network, and each node would host a copy of the BlueSky protocol.

Sources

Akomolafe, A. C., Molefi Kete Asante, & Nwoye, A. (2017). We will tell our own story: The lions of Africa speak! Universal Write Publications Llc, C.

Amartya Sen. (2011). Development as freedom. New York, N.Y.: Anchor.

Armstrong, M. (2016, November 17). Infographic: Fake news is a real problem. Statista Infographics.

Associate Press. (2023). AP Fact Check. AP News.

Barthel, M., Mitchell, A., & Holcomb, J. (2016, December 15). Many Americans believe fake news is sowing confusion. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project.

BBC. (2018, December 17). Russia “meddled in all big social media.” BBC News.

Belluz, J. (2015, April 19). How we got duped into believing milk is necessary for healthy bones. Vox.

Borella, C. A., & Rossinelli, D. (2017). Fake news, immigration, and opinion polarization. SocioEconomic Challenges, 1(4), 59–72.

Bursztynsky, J. (2021, July 20). White House says social media networks should be held accountable for spreading misinformation. CNBC.

Edwards, L. (2022). How to regulate misinformation. Royal Society.

Erwin, S. (2020, November 9). SpaceX explains why the U.S. Space Force is paying $316 million for a single launch. SpaceNews.

Forrester. (2023, February 28). Fundamental problems on social media platforms. Forbes.

Frenkel, S. (2023, April 28). What is Bluesky and why are people clamoring to join it? The New York Times.

Garrett, D. / K. (2023, April 21). What is Bluesky? The Twitter alternative with promising networking technology. Decrypt.

Gielow Jacobs, L. (2022). Freedom of speech and regulation of fake news. The American Journal of Comparative Law, 70(Issue Supplement_1).

Grush, L. (2023, February 3). SpaceX awarded shared NASA contract worth up to $100 million. Bloomberg.com.

Hamilton, K. (2023, April 27). Twitter has complied with almost every government request for censorship since Musk took over, report finds. Forbes.

Hopper, T. (2018, March 7). Could Jordan Peterson become the best-selling Canadian author of all time? National Post.

Jerit, J., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Political misinformation. Annual Review of Political Science, 23(1), 77–94.

Kessler, G. (2017, January 1). About The Fact Checker. Washington Post.

Kozyreva, A., Herzog, S. M., Lewandowsky, S., Hertwig, R., Lorenz-Spreen, P., Leiser, M., & Reifler, J. (2023). Resolving content moderation dilemmas between free speech and harmful misinformation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(7).

Lowrey, A. (2018, September 29). Are immigrants a drain on government resources? The Atlantic.

Malik, K. (2023, January 1). The Twitter Files should disturb liberal critics of Elon Musk – and here’s why. The Observer.

Mattoo, S. S., & Shashank. (2022, February 21). Big tech vs. red tech: The diminishing of democracy in the digital age. Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Meek, A. (2022, June 22). The Daily Wire, which now boasts 890,000 paid subscribers, signs Jordan Peterson to its new DailyWire+. Forbes.

Mekemson, C., & Glantz, S. A. (2002). How the tobacco industry built its relationship with Hollywood. Tobacco Control, 11(Supplement 1), i81–i91.

New York Times. (2019). Ethical journalism. The New York Times.

McCarthy, N. (2018, June 14). Infographic: Where exposure to fake news is highest. Statista Infographics.

Palmer, A. (2019, December 11). Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey has an idealistic vision for the future of social media and is funding a small team to chase it. CNBC.

Paul, K. (2020, October 30). Here are all the steps social media made to combat misinformation. Will it be enough? The Guardian.

Peters, M. A. (2017). The information wars, fake news and the end of globalization. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(13), 1161–1164.

Reuters Fact Check. (2022, April 20). Fact check-video claiming BlackRock and Vanguard “own all the biggest corporations in the world” is missing context. Reuters.

Reuters Staff. (2017, February 19). Suppressing free press is “how dictators get started”: Senator McCain. Reuters.

Robison, K. (2023, April 2). Elon Musk’s open source code is “completely dishonest.” Fortune.

Rutherford, A. (2020). How to argue with a racist. The Experiment.

Sherman, A., Trisi, D., Stone, C., Gonzales, S., & Parrott, S. (2019, August 15). Immigrants contribute greatly to U.S. economy, despite administration’s “public charge” rule rationale. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Rosenthal, S., & Maibach, E. (2017). Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Global Challenges, 1(2), 1600008.

Vanderwicken, P. (1995, May). Why the news is not the truth. Harvard Business Review.

Vese, D. (2021). Governing fake news: The regulation of social media and the right to freedom of expression in the era of emergency. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 13(3), 1–41.

Vraga, E. K., & Bode, L. (2020). Defining misinformation and understanding its bounded nature: Using expertise and evidence for describing misinformation. Political Communication, 37(1), 136–144.

Wallace-Wells, B. (2023, January 11). What the Twitter Files reveal about free speech and social media. The New Yorker.

WebFX Team. (2019, September 12). The 6 companies that own (almost) all media [Infographic]. WebFX Blog.

West, J. D., & Bergstrom, C. T. (2021). Misinformation in and about science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(15), e1912444117.